Combating domestic violence: Strong networks, safe homes

Domestic violence is usually associated with physical or verbal altercations. But, as Paul Skelton and Brihony Tulloch reveal, smart devices are paving the way for a new kind of spousal abuse.

Domestic violence is usually associated with physical or verbal altercations. But, as Paul Skelton and Brihony Tulloch reveal, smart devices are paving the way for a new kind of spousal abuse.

The internet and all the benefits that come with it are part of our everyday lives.

Buoyed by smart phones, the Internet of Things (IoT) and the ‘home assistant’ (Google Assistant, Apple HomePod, Amazon Alexa), accessing technology in the home has never been easier.

But what happens when this technology becomes a means of domestic abuse?

ADVERTISEMENT

A startling new trend in domestic violence is emerging, and residential integrators may soon need to reassess their role in educating clients on cyber safety.

In Australia, one in three women and one in five men have experienced domestic violence in some form during their lifetime. The Australian Bureau of Statistics says 264,028 domestic violence incidents were reported and recorded between 2014 and 2016. However, it is thought that 90% of instances are not reported to the authorities.

Now, the rapid uptake of IoT devices is making it even easier for abusers to extend control over their victims.

Women’s Services Network (WESNET) national director Karen Bentley says smart home technologies are being increasingly used for domestic abuse.

“Perpetrators will find all sorts of innovative ways of behaving badly,” Karen says.

“It seems that every new form of technology is likely to be misused by people who are abusive.”

A June 2018 article in the New York Times by Nellie Bowles, titled Thermostats, Locks and Lights: Digital Tools of Domestic Abuse, drew attention to the burgeoning issue.

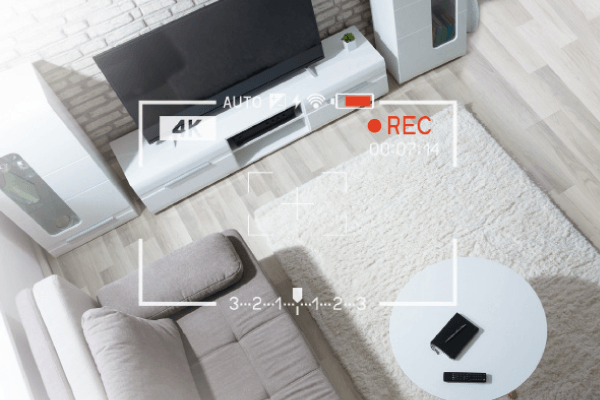

Lights turning on and off, loud music blasting in the middle of the night and door lock access codes changing are just some of the disturbing examples of abuse via technology.

Some home assistants and remotely accessible security devices make it possible for abusers to visually monitor their victims.

“Connected home devices have increasingly cropped up in domestic abuse cases over the past year, according to those working with victims of domestic violence,” the article stated.

“Those at help lines said more people were calling in the past 12 months about losing control of WiFi-enabled doors, speakers, thermostats, lights and cameras. Lawyers also said they were wrangling with how to add language to restraining orders to cover smart home technology.

“The people who spoke to The Times about being harassed through smart home gadgetry were all women, many from wealthy enclaves where this type of technology has taken off.

“Each said the use of internet-connected devices by their abusers was invasive – one called it a form of ‘jungle warfare’, because it was hard to know where the attacks were coming from. Women also described it as an asymmetry of power because their partners had control over the technology – and, by extension, over them.

“One of the women, a doctor in Silicon Valley, said her husband, an engineer, controlled the thermostat. ‘He controls the lights. He controls the music. Abusive relationships are about power and control, and he uses technology.’

“She did not know how all of the technology worked or exactly how to remove her husband from the accounts. But she dreamed about retaking the technology soon.”

A 2015 survey undertaken as part of the ReCharge: Women’s Technology Safety project shows that 98% of practitioners in the domestic violence field had clients who had experienced abuse via technology.

The project is a collaboration between Women’s Legal Service NSW, Domestic Violence Resource Centre Victoria and WESNET, funded by the Australian Communications Consumer Action Network.

In general, surveyed practitioners felt that perpetrators would exploit any perceived vulnerabilities and could effectively use technology to further isolate their victims.

When practitioners were asked how stalking and abuse via technology affected the victims, one of the key themes was the anxiety created in victims’ lives and a sense of remaining on high alert.

One practitioner said it added to the victim’s anxiety and hyper-vigilance to think that the perpetrator seemed to be everywhere. The victim felt unable to get away from the perpetrator, even after leaving the relationship.

Non-physical abuse – such as that facilitated by technology, or stalking – may be considered less serious than other forms. However, stalking by an intimate partner has been linked to an increased risk of homicide.

One 2002 study found that 68% of women experienced stalking in the 12 months before an attempted or actual homicide. The most frequent types of such stalking included following, spying, unwanted phone calls and keeping the victim under surveillance.

Karen Bentley says the greatest concern surrounding smart home technology is general privacy and security.

“Everybody needs to be thinking about this when they have any kind of device that connects with the internet. The more that we can help women – who may not be as tech-savvy as men – understand, the better.”

Home routers and security cameras generally have little or no built-in security, making them vulnerable to malware, so users are already on the back foot.

“Most technology companies are building these devices to make life easier, more connected and to improve people’s experiences,” Karen says.

“But sometimes they’re not thinking about what happens if these products are misused.”

For example, a WiFi router acts a ‘front door’ to smart home devices. Like any front door, it should be solid and equipped with strong locks to keep residents safe.

Some users may not realise that a perpetrator who has shared a home or any device with them could have easy access to devices or accounts if there are no privacy settings in place.

An abusive person can also misuse an IoT device simply by downloading spyware or hacking into the device, network or linked account.

Karen says the answer is not to tell women that they shouldn’t use technology – it’s education.

“Anything that helps a person’s understanding of how to protect their privacy and security is really valuable.”

End users taking responsibility for their IoT device and security is all well and good, but integrators do have a role to play. They are often in the best position to educate end users on how to maintain online safety.

Realistically, enabling solid privacy settings during installation comes under the banner of good customer service. A few simple steps can give clients peace of mind and reduce the risk of technological abuse.

Systems integrators should consider:

- Creating a separate network

Only business-class routers and some kinds of home routers have guest network capability built in. If possible, this separate network should be used for connecting IoT devices, as it will give greater control over the security settings. - Rotating strong passwords

Ensure that WiFi networks and accounts linked to any IoT devices have strong passwords that are changed every three months. - Regularly updating IoT devices

Software updates include security improvements, so it’s vital that users regularly check for available updates to give devices increased protection against hacking or spyware. - Ensuring the strongest configurations are enabled

The proper configurations will make sure the WiFi hotspot supports only the most up-to-date protocols for transmitting information. Opt for the WiFi Protected Access 2 (WPA2) security algorithm instead of a Wired Equivalent Privacy (WEP) algorithm or standard WPA. The only encryption method that should be enabled is the Advanced Encryption Standard (AES). Completely disable WiFi Protected Setup (WPS) and anything related to the Temporal Key Integrity Protocol (TKIP), as it allows for another way of connecting without the password. - Identifying network devices

An important step is to identify (and provide a list of) all devices connected to the IoT network.

Strong security protocols and software are usually not a high priority for manufacturers of smart devices. Therefore, it’s even more important for systems integrators to educate consumers about their exposure, either during installation or via external means such as apps.

Apps such as Fing for iOS and PingTools for Android scan devices to see who is connected to a network or router if the perpetrator is near the victim’s network. However, they don’t always work over a greater distance.

Karen says the first step WESNet takes when working with victims is to identify all devices connected to a network.

“When we’re working with female survivors of abuse via technology we also look at their privacy and security settings, and make sure that they’re not being accessed by somebody else.

“What we would really like to see is assistance for people to be more aware of their privacy and security.”

Domestic violence prevention should always be focused on abusers bearing the responsibility for their illegal actions, but the solution to technological abuse is not always simple.

“It’s hard to have a ‘one size fits all’ solution, because every woman is in a different situation. What we’re trying to focus on is holding abusers accountable, as well as educating women and technology professionals about the risks.”

As it stands, end user education by systems integrators is one of the best tools available when it comes to reducing the risk of technological abuse.

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT