A snapshot in time: NEC facial recognition technology identifying lost soldiers

The 2020 ANZAC Day dawn service was conducted online for the first time ever. It was also the first time a number of previously unidentified soldiers have been recognised. Sean Carroll finds out more.

In 1916, in the middle of World War I, in a small town called Vignacourt in Northern France, Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, a farming couple, purchased a camera and decided to set up a makeshift photography studio in their home village.

Vignacourt happened to be a place that saw many Australian soldiers pass through seeking relief, a warm bath and time off behind the front line.

ADVERTISEMENT

The Thuilliers would take the opportunity to photograph these men and women, some in single portrait form, some in groups of dozens and even more than 100 of their mates in the open air and convert the images from glass negatives into postcards that the diggers could write on and send home to their families, always desperate for news of their loved ones so far away.

After the war, the photographs taken by the couple were packed away and placed in the attic of their barn without any labels or names below.

In the early 2010s, WA-based philanthropist and Seven Group Holdings executive chairman Kerry Stokes heard about these glass negatives, purchased a number of them and donated them to the Australian War Memorial (AWM) in Canberra.

These images were toured around the country at various locations under the show name ‘Remember Me: the lost diggers of Vignacourt’. The collection toured for approximately seven years and asked family members to manually identify some of the pictured soldiers. It was a painstaking process that saw just over 100 soldiers identified.

Keen to assist in recovering a piece of lost history, electronics and technology company NEC approached the AWM with its facial recognition technology and other projects used on historical records. From there, the AWM began to consider the idea of using the technology for the Vignacourt collection.

“The AWM was impressed enough at the accuracy levels of the NEC algorithms to take that next step. We entered into a memorandum of understanding and then did the work,” NEC senior consultant, privacy and security business technology advisory Sylvia Jastkowiak says.

“We utilised two larger photographic databases held by the AWM, one called the E-Series and the Darge Series, and use them as our reference databases. So we tested the unidentified Vignacourt images against these two other larger scale databases.”

The NEC facial recognition technology matched faces of these images with ones in the AWM collection that the memorial had already identified.

Sylvia says that while NEC was there for the project, the team was able to run through two pools of unidentified soldiers from other collections as well.

“The hits that we got were incredible,” she says.

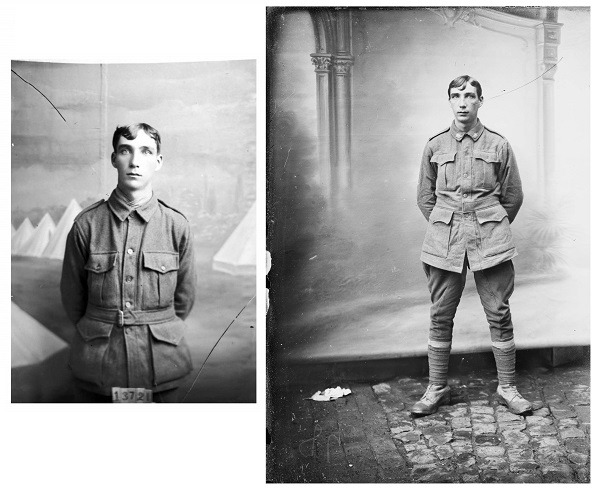

Private Robert Deegan recruitment photo (left) and one year later (right)

“We gave them the top results from all test pools, so we had three groups of unidentified soldiers but specifically for the Vignacourt collection, we had 1,038 potential matches come back to us and then they decided to go on to validate around 100 of those, of those top results.”

The first of these hits was of a young soldier from country Victoria, Private Robert Deegan. The team at NEC was able to match his recruitment photo from when he had just signed up to the Vignacourt image.

While it was clear that just over a year of war had taken a toll on his young face, the match was undeniable.

The total trial took two days and in just that short amount of time, it hit upon more than ten-times the potential matches compared to the seven years of manual verification when touring the images.

“With some of the cases, they either didn’t have the historical records to be able to confirm 100% that it was correct, but that’s just the issue with manual verification sometimes,” Sylvia explains.

Manual verification is very labour-intensive and there currently isn’t any technology that can automate the process at a high enough level.

The successful trial is quite important as Sylvia points out that the records, including video footage, is deteriorating faster than anyone can manually sort through and record. Using facial recognition technology is faster and in turn, puts less physical strain on the images themselves.

“It isn’t really surprising that the trial worked because when you see the quality of some of these images, they’re so good, they’re probably better than photos taken with your iPhone,” Sylvia explains.

“They’re quite standardised which is great because you’re not capturing people in informal situations, most of the time they’re either prepared to take a formal photo with their battalion or their group, or they’ve gone into a photographic studio like the Vignacourt collection, where they’re prepped and primed for a photo.”

The Vignacourt collection of images is certainly an extremely rare find but NEC now understands the ability of its facial recognition technology.

Sylvia and NEC are interested in seeing further applications of this technology and how it can scale up and how it can get past the labour-intensive process of manual verification.

“I think you would have to do some sort of smaller investigation just to make sure that dates align. For example, you’d need to check if records say the soldier was deployed in a certain country and check where the image was taken,” she says.

“The opportunities are endless once you open the Pandora’s Box.

“You think about all the records or all the museums in Europe, in the US, Asia or even universities as well. It’s quite exciting.”

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT

-

ADVERTISEMENT